CLUBS

From the 1840's until the early 1930's hickory was the preferred shaft for golf clubs worldwide. Hickory shafts prevailed during a period that saw the most radical changes in the history of the game. As the ball developed from feathery to gutty and then from Haskell to rubber, golf club design evolved to meet the demands of each period.

Early club shafts were made of Ash but the introduction of golf to the United States in the 1840's uncovered hickory as a more suitable, readily available alternative. The foremost requirement of a wood shaft was durability. This meant that the timber had to provide enough flex to generate "whip" to the swing but also enough stiffness to withstand striking (the ball) and impact with the ground without breaking. Hickory's tremendous strength and straightness endeared it to golfers and saw it remain the single constant in golf club construction for over 90 years.

By the turn of the 20th century hickory clubs were being made in huge quantities in both Great Britain and the United States. By the end of the hickory era in the early 1930's there were literally millions of clubs available. Many of these clubs remain and with a little TLC are as good to use today as they were when they were first made.

The majority of clubs originate from Scotland or the US with a few locally made clubs. As was the norm during most of the hickory era very few of the clubs are from matched sets, a trend that started to appear towards the end of the hickory period when large US companies such as Spalding and MacGregor dominated the market.

The majority of clubs originate from Scotland or the US with a few locally made clubs. As was the norm during most of the hickory era very few of the clubs are from matched sets, a trend that started to appear towards the end of the hickory period when large US companies such as Spalding and MacGregor dominated the market.

In hickory times clubs were often purchased individually and routinely from more than one maker. Terms such as "swingweight", "shaft flex" and "torque" didn't exist in the hickory era and clubs were largely chosen based upon feel. Bobby Jones' playset was sourced from several makers (both Scottish and US origin), each club individually made to suit his exact requirements.

Hickory facts

Hickory is a tree (hardwood), comprising the genus Carya, most commonly found in the United States.

Hickory is very hard, stiff, and dense. As hickory golfers we know it was the golf shaft material of choice from the mid 1800’s until the late 1920’s. Today it is used for a variety of purposes including tool handles, drumsticks, lacrosse stick handles etc.

To understand the effects of aging and storage conditions on hickory golf clubs we need to delve into the science of timber. Most of this research relates to the structural integrity of timber over long periods particularly in relation to use in construction. The processes that can occur in hardwood structural timbers correlate to the effects of aging and storage conditions on hickory shafts.

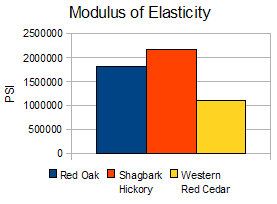

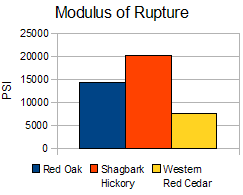

There are two measurements that are commonly used to indicate the mechanical qualities of timber.

The first, Modulus of Elasticity (MOE), measures a wood’s stiffness, and is a good overall indicator of its strength.

Modulus of elasticity (MOE)

Technically it’s a measurement of the ratio of stress placed upon the wood compared to the strain (deformation) that the wood exhibits along its length. Hickory is known to have excellent MOE strength properties among domestic species in the US.

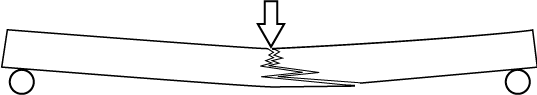

The second, Modulus of Rupture, frequently abbreviated as MOR, (sometimes referred to as bending strength), is a measure of a specimen’s strength before rupture. It can be used to determine a wood species’ overall strength; unlike the modulus of elasticity, which measures the wood’s deflection, but not its ultimate strength. (That is to say, some species of wood will bow under stress, but not easily break). Hickory is known to have excellent MOR strength properties among domestic species in the US.

Modulus of rupture (MOR)

There are timbers that are stronger and harder than hickory but none have the unique combination of strength and toughness that make it an ideal choice as a golf club shaft.

The main chemical components constituting wood cell walls are cellulose, lignin and hemicelluloses. Cellulose is a carbohydrate macromolecule that represents 40-45 wt% of the wood, being slightly higher in hardwoods than in softwoods. The cell walls in timber are composed of multiple layers. The framework of the cell walls is provided by cellulose fibres, while hemicelluloses and lignin constitute an encrusting matrix. The three main parts are the middle lamella (ML), the primary cell wall (P) and the secondary wall (S).

Due to the crystalline structure of the cellulose, the alignment of microfibrils in the cells and the alignment of cells in the stem wood, an important property of wood arising from this ultrastructure is its hygroscopicity. Hygroscopicity is the measurement of a material’s ability to absorb or release water as a function of humidity. Being a capillary-porous material, timber is able to adsorb and desorb water depending on the climatic conditions. The water can be located either in the lumen (free water) or within the cell wall (bound water).

The state in which no free water is present in the lumina (free water) while the cell walls are saturated (bound water) is called the fibre saturation point and the moisture content stabilized at a certain climate is termed equilibrium moisture content (EMC). EMC is more commonly known as “fully seasoned”. In most cases the mechanical properties of an individual timbers species are optimal at the EMC (when it is fully seasoned). Below the fibre saturation point, a change in water content results in shrinkage of the material and has an influence on its physical and mechanical properties.

The state in which no free water is present in the lumina (free water) while the cell walls are saturated (bound water) is called the fibre saturation point and the moisture content stabilized at a certain climate is termed equilibrium moisture content (EMC). EMC is more commonly known as “fully seasoned”. In most cases the mechanical properties of an individual timbers species are optimal at the EMC (when it is fully seasoned). Below the fibre saturation point, a change in water content results in shrinkage of the material and has an influence on its physical and mechanical properties.

Aging is the irreversible change of physical and mechanical properties of a material during longer storage or usage. Deterioration may occur because of climatic and environmental factors, but also through wood destroying organisms (insects, fungi, bacteria and borers) The changes in physical and mechanical properties of timber due to aging occur from changes in the microstructure and in effect from chemical changes in the cellular components. Since storage conditions determine what kind of chemical processes may occur, it is obvious that they have a significant effect on the aging process.

Timber exposed to direct sunlight undergoes chemical degradation caused by UV radiation. Lignin is the cell wall component most sensitive to UV-light. Lignin transfers the UV-light to cellulose resulting in the degradation of cellulose. Besides photodegradation, surface thermal degradation also has to be taken into account as the surface temperature of wood stored outdoors can reach 60-90°C depending on its colour. Timber exposed to weathering is also subjected to mechanical stresses due to fluctuations in temperature and humidity. Fast changes in the relative humidity can generate an uneven moisture distribution in timber, which leads to the formation of moisture-induced stresses that may cause structural damage.

Timber is most stable when stored indoors in dry air. Favourable conditions (low temperature and UV radiation, no contact with liquid water, stable humidity conditions) are shown to result in minimal structural aging effect. Unless hickory clubs are left laying outdoors exposed to the elements then the greatest concern regarding the preservation of hickory shafts, particularly over many decades, is the avoidance of extreme heat and dry conditions (low humidity).

As an organic material the degradation of timber over time is inevitable and failures at the microscopic level can be present even in wood that seems to be macroscopically intact. The microstructure of wood stays intact only in exceptional cases. The good news for hickory golfers is this process can take hundreds of years to occur.

Most of the strength properties of timber seem to change rather slowly with aging, or not at all. However, the fracture behaviour of aged timber is often found to be different to that of new timber. Timber appears to become more brittle with aging. Many authors report a decrease in the absorbed energy in the impact bending test (MOR) for aged timber.

For hickory golfers this may manifest itself in two ways. Firstly, as period shafts age they may become slightly stiffer compared to their performance as a new shaft. Second, is a cracked or broken shaft from what appeared to be a period hickory shaft in good playable condition.

How does this happen?

The theory is that once the moisture content of the timber drops below the EMC, water is removed from the cell wall and irreversible damage to the cell occurs. The greater the amount of water removed, the greater amount of cell damage. Restoring the moisture content after a cell is damaged will not repair the damage already done, think of it like applying moisturiser after getting sunburned, too little too late. The level of damage is directly proportional to the number of cells affected. The thing to remember is that degradation of cells is a naturally occurring process but one that can be significantly accelerated by environmental factors.

So what does this all mean and how do we prevent it?

Every period hickory shaft will have a level of age related damage even if stored under ideal conditions. In terms of playability the damage will vary from having no perceivable difference to that of a modern hickory shaft to those who’s only use is as firewood. The problem is being able to distinguish a playable shaft from one that will not handle the rigours of hickory play. Clubheads that are heavily rusted with badly warped or discoloured shafts suggest a less than ideal storage environment and should be viewed with a level of suspicion if they are to be used for play.

When choosing clubs for play inspect the shaft closely. Look for surface cracking or signs of weathering such as discolouration and flaking varnish. Many shafts with a level of age related damage will be easily to identify, others may prove more difficult. A few will only reveal the true extent of their history after the first hit. I have had my fair share of shafts with no external signs of damage that have split in two with the first hit.

Considering the vast number of clubs produced during the hickory period there are still literally thousands of period clubs that are more than capable of being used for their intended purpose.

The greatest concern for the preservation of hickory shafts are the conditions under which they are stored. It’s reasonable to expect that the set of clubs that has been leaning inside Grandad’s tin shed for the last 90 years is probably not going to be in as good a condition as the set that has been locked away in the hallway cupboard for the same period. As mentioned above, timber is most stable when stored indoors in dry air away from extreme variations in temperature and humidity.

One point to I would like to make, especially to those within the hickory playing community who claim “period only” clubs are the true representation of the sport and view modern hickory clubs as having an unfair advantage, is the simple fact that golfers from the hickory era were not using shafts that were already up to 100 years old. The truth of the matter is if you want to guarantee a hickory golf experience as it was played by Jones, Vardon et al then you will need to be using new hickory shafts.

My playset is made up of period clubs with a mixture of original and new hickory shafts. Some shafts were replaced due to breakage others because the shaft simply didn’t suit my swing. Neither shaft type has any discernible advantage or disadvantage compared to the other.

What part does the surface treatment (oils, shellac etc) of the shaft play in its performance and protection?

Substances applied to the exterior of the shaft penetrate only fractions of millimetres and have no direct influence on the timber beyond this. Apart from acting as an aesthetic protective barrier, surface finishings also act as a water barrier by slowing the sorption processes. Apart from playing in wet conditions, protecting hickory shafts against large fluctuations in humidity is probably not that much of a concern unless you're travelling to and from places with large differences in climate.

Oils, such as Tung or Linseed, applied to the surface DO NOT soak in and condition the shaft as some people believe. Greater penetration into the timber can only be achieved by soaking or boiling and I doubt whether this would be an option for hickory golf clubs.

These oils cure and harden by undergoing a chemical reaction (oxidation) to form a hard protective barrier on the surface of the timber. Other commonly used finishes such as shellac and polyurethane also act as surface protection for the hickory shafts. Different surface finishes offer a distinct “look” with varying levels of durability and protection. Most of us choose the finish that we prefer knowing that they all perform the required task with varying degrees of effectiveness and maintenance. Solvent based polyurethane provides the hardest and most durable protective coating.

Replica clubs vs original clubs

As the number of people playing with and/or collecting hickory clubs is increasing the availability of authentic clubs is obviously diminishing. This causes two major issues. The first is the preservation of historically significant clubs. As more and more players seek out authentic hickory clubs for use a greater number of collectible clubs will find their way onto the course where they are exposed to potential damage. This is of particular concern in Australia where the number of historically relevant clubs is very limited.

The second issue relates to the affordability of authentic clubs. As the pool of remaining playable clubs shrinks the cost to new players looking to buy a quality set of period clubs is constantly increasing. Sought after individual clubs can sell for as much as $200-$300 in the US.

Recognizing the impact that restricting hickory play to authentic clubs would have on the prosperity of hickory golf, SoHG acted to allow the use of "replica" hickory clubs along with the refurbishment of pre-1935 steel shafted wood clubs (with new hickory shafts) in official SoHG competitions. As a result hickory players now have additional clubs to choose from, whether it be a new player looking for their first set of clubs or an established player looking to preserve much loved authentic clubs. In performance terms, replica clubs or re-shafted woods offer no advantage over properly maintained authentic clubs. The designs of replica irons and woods are based upon actual hickory period clubs.

Hickory Golfers supports the playing and equipment guidelines established by SoHG and recommends those interested in purchasing replica clubs visit Tad Moore's hickory website.

A Final Word

Hickory Golf can be as formidable as it is fun.

Hickory Golf can be as formidable as it is fun.

Hickory golf is not about computer designed, low-torque, nano-technology, carbon fibre, frequency matched, high modulus, mid-kick point, boron-graphite shafts! It's not about hitting driver then wedge to a 420m par 4. Forget about launch monitors, deflection profiles, GIR's and putting statistics.

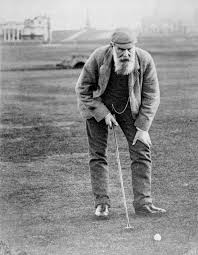

Hickory golf is about managing your way around a golf course with six or seven clubs, the same way the pioneers of the game did 100 years ago. Harry Vardon won his record breaking 6 Open Championships using only 7 clubs. Joe Kirkwood won the 1920 Australian Open with the same number. Hickory golf is about using your imagination to create shots that we rarely use in the modern game. It's about forgetting the score and embracing the individual challenge of the course.

It is a game where sometimes the clubs can be as unpredictable as the swing that drives them. Most who try Hickory golf are intrigued by the vagaries of the game and will find themselves drawn back to explore it time and time again.

Whatever your reasons for playing you will have had the rare opportunity to experience golf from a time in history when true legends of the game were shaping its future.